manipulating exercise protocols for specific adaptations

Exercise — just like any activity we do in daily life — causes our body to adapt by triggering a cascade of physiological events. When we look at different people and athletes, we can see how versatile the human body is.

This suggests that different movements (a.k.a. exercise) cause different adaptations. If we want to set a goal for ourselves, we have to know how to manipulate exercise variables to trigger the adaptations we desire.

There Are 3 Key Components to Consider When Trying to Elicit Specific Adaptations:

1. The way your body responds to exercise depends on how much muscle tissue you activate.

Let’s unpack that...

Imagine doing 10 reps of a back squat at 80% of your 1RM. As you progress through the set, your heart rate spikes, your breathing rate increases, and by the end, you likely feel drained — ready to sit or even lie down.

Now imagine performing that same protocol (80% 1RM for 10 reps), but with bicep curls. Your arms will definitely burn, but the rest of your body won’t feel nearly as tired. Your heart and breathing rate won't get nearly as elevated.

And here’s where it gets interesting…

The more muscle tissue you activate, the more help your body needs to recover, adapt, and grow:

- Hormonal signaling ramps up to repair muscle, replenish energy, and clear waste.

- Heart rate and respiration increase to deliver oxygen and nutrients.

- Muscle cells become more sensitive to anabolic hormones like testosterone and growth hormone.

- Neural signaling in the CNS becomes more coordinated between muscles.

With all this signaling, muscles grow stronger, larger, and more powerful. Their architecture changes. Inside each muscle cell, energy storage, enzymes, and mitochondria increase. And when many muscles are activated simultaneously, the CNS also improves intermuscular coordination.

That’s why free-weight compound exercises are more taxing — but also superior — for building strength, power, coordination, and even aerobic capacity.

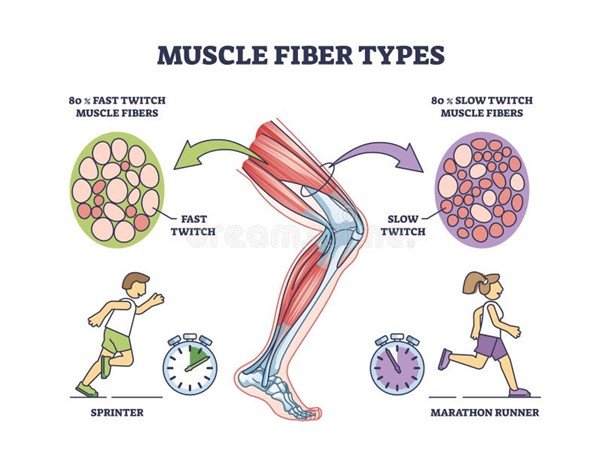

2. Different muscle fiber types create different demands.

Our muscles consist of many cells (called fibers). Not all fibers are the same. Muscle contains a continuum of fibers — from slow-contracting, low-force, fatigue-resistant fibers to fast-contracting, high-force, quickly-fatigued ones.

When we move, the CNS activates the most efficient fibers for the task:

- Slow fibers activate during low-intensity, long-duration tasks.

- As the demand for force or speed increases, fast fibers are recruited.

The slower a fiber contracts, and the less force it produces, the more it relies on aerobic energy. The faster a fiber contracts, and the more force it generates, the more it depends on anaerobic energy systems.

This difference in energy demand leads to different adaptations.

3. Manipulating intensity, volume, and rest changes everything.

Even with the same exercise, changing just one of these variables can lead to very different results:

- High intensity + low volume favors strength and power with minimal hypertrophy.

- High volume + moderate intensity supports hypertrophy and muscular endurance.

- Changing tempo (e.g., slow eccentrics, paused reps) manipulates stability, tension, and muscle damage.

- Longer rest allows for greater recovery and total output.

- Shorter rest increases fatigue, fiber recruitment, and aerobic or anaerobic endurance adaptation.

This is why how you train — not just what you train — determines your progress.

References

- Hawley, J. A., & Gibala, M. J. (2012). What’s new since Hippocrates? Preventing type 2 diabetes by physical exercise and lifestyle intervention. Diabetologia, 55(3), 535–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-011-2413-1

- Kraemer, W. J., & Ratamess, N. A. (2004). Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Medicine, 34(5), 339–361. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200434050-00004

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res, 24(10), 2857–2872. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3

- Hackney, A. C. (2006). Stress and the neuroendocrine system: the role of exercise as a stressor and modifier of stress. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab, 1(6), 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1586/17446651.1.6.783

- Schiaffino, S., & Reggiani, C. (2011). Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev, 91(4), 1447–1531. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00031.2010

- Ratamess, N. A., et al. (2009). Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 41(3), 687–708. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670

- Brooks, G. A., Fahey, T. D., & Baldwin, K. M. (2005). Exercise Physiology: Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Ahtiainen, J. P., et al. (2005). Muscle hypertrophy, hormonal adaptations and strength development during strength training in strength-trained and untrained men. Eur J Appl Physiol, 89(6), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-003-0833-3